Nathan Tweed quit the studio in the strike’s second week and moved back to the Midwest. He joined his father’s greeting card business. Occasionally, he would send Rollie samples of his work. His cards were head and shoulders above anything Rollie’d ever seen in a drug store. Tweed died in a car crash in the mid-1950s. The other driver was pickled and walked away without so much as a bruise.

After what became known as “The Adello Incident”, Rollie carried a blackjack in his pocket. Fortunately, he was never again brained with citrus, but better safe than sorry.

Both Joey Adello and Bill Scanlon died in the Pacific theater of the Second World War. Both men had volunteered immediately after Pearl Harbor.

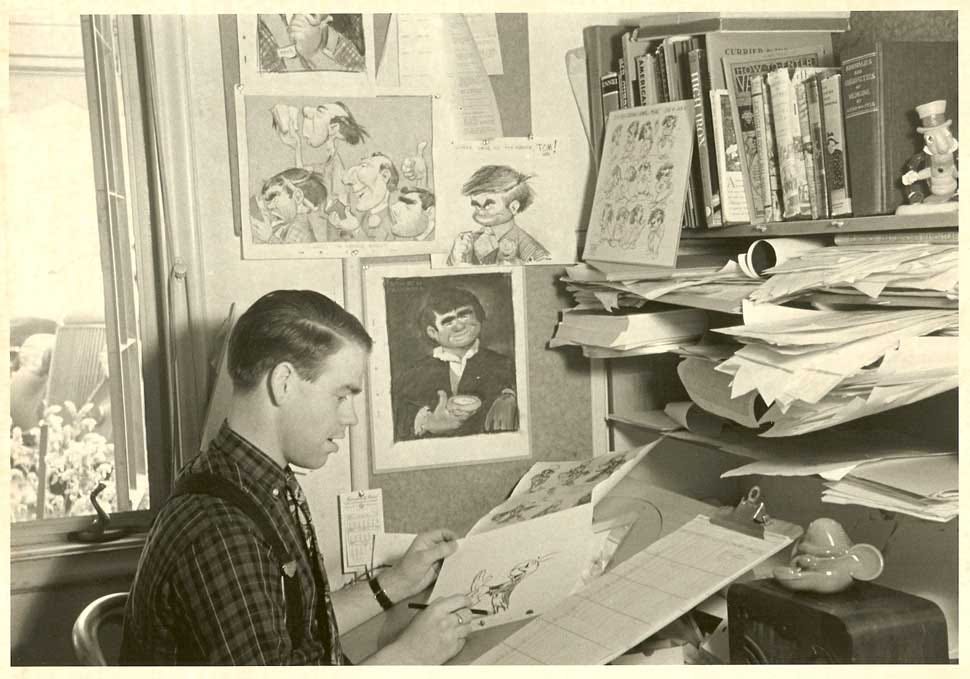

Rollie worked hard during the strike. All of the scabs did. His daily output was mechanical and uninspired—more so than usual, he thought. The atmosphere at Disney’s had a deep effect on the former Daytonian. The strike catalyzed his move from shorts into feature films, and he sat doing scenes every day for Dumbo. He should have been walking on air, but he simply wasn’t. He no longer had the trusted eyes of his office mates.

He wasn’t friendless during those days. Gary Dunmeyer—a supervisor with almost no one to supervise—spent a lot of time in Prader’s office. He missed the esprit de corps of the Silverlake days and often described the Burbank move as a cancer.

One day, Rollie found Dunmeyer in the lobby of the animation building, staring up at the ceiling. He thought the older man might be in the midst of a stroke. “Whatcha doing there, Gair?”

Gary didn’t speak. He just pointed up.

Prader looked up to see an ugly black spot on the ceiling. “Water damage,” he said.

Dunmeyer shook his head. “Cancer.”

Rollie looked again. “Pretty sure it’s water damage.”

“Don’t be naive,” the supervisor said, inhaling through his nostrils. Can’t you smell it? It smells like death.”

Rollie looked a moment longer and took the hall to the right. “You’re a real laff riot, Gary.”

Forgetting the alleged cancer, and with nothing else to do, Dunmeyer followed Prader. Rollie flipped on his overhead light and could see that there was something off. There were two sheets of animation paper he’d crumpled and thrown into the trash now uncrumpled and taped to his desktop. Written in the margins of one of them was, “Rollie, stop throwing out the good stuff! These drawings are pure gold!” Confused, he showed the rescued pages to Gary.

When he saw them, Dunmeyer laughed. “Way to go, kid! You’ve graduated into the big leagues.”

“I don’t understand,” Rollie said.

“Back in the old days, Walt would prowl the halls at night and look at everyone’s work. He would also pick through their trash looking for discarded gems. I thought he’d lost interest, but he was in here last night.”

“Is this supposed to be a badge of honor?” Prader asked, not sure what to do with the drawings Walt gave his seal of approval to.

Dunmeyer sat down in the soon-to-be-late Bill Scanlon’s chair and shrugged. “You know as well as anyone Walt is stingy with his praise. He liked those two drawings and told you so.”

Rollie decided to be flattered, though he put the two smoothed-out sheers aside. He sat down and turned on the light underneath his desk.

“Have you heard the latest?” Dunmeyer said.

“Gossip, Gary? Isn’t that beneath you?” The artist picked up a Blackwing pencil and sharpened it.

“I’m only a man, born to sin.”

“Very Old Testament.”

“I wouldn’t know. I’m of the Jewish persuasion.”

“Isn’t the Old Testament just the Torah?”

“Search me. Walt and some of the other artists are getting ready to leave the country. At the State Department’s request.”

Prader turned to face the older man, blowing shavings from the tip of his pencil. “The State Department? Since when is Walt in the spy business?”

“Not a spy, a diplomat.”

Rollie laughed. “A diplomat? Has the State Department seen what’s going on out in the street?” He meant the ongoing picket lines.

“I concede the irony, but only on a local level. Internationally, the name ‘Walt Disney’ still has a lot of cachet.”

“Where’s he going?”

Dunmeyer shifted lower in the seat, getting comfortable. “South America. Central America.”

Rollie placed a new sheet of paper onto the pegs at the bottom of his drawing surface, covering the drawings from the day before. The light underneath shone through so Rollie could see all of the sheets in relation to one another. He was working on a scene with a mouse in a circus outfit. “Uncle Sam is unhappy with the Nazis poking around south of the border.”

“Uh-huh. Walt might be the perfect antidote to Der Führer.”

“Or they want to fight fascists with fascists.”

Gary grinned. “You don’t mean that.”

“No,” Prader agreed, putting pencil to paper. “Gary?”

“Yes?”

“It’s time for you to go.”

Gary sighed and stood. “You and your damn Protestant Work Ethic.”

Prader’s wife and adopted daughter called him “Sad Sack” behind his back. Every day, he came home, ate dinner, stared vacantly for a couple of hours, then went to bed. This behavior would have continued for all four months of the strike if he hadn’t been confronted.

By his adopted daughter.

That night, during Rollie’s round of catatonia, Molly stood in front of him. “Hello?” she said.

“Hello? Yes?” Prader said, snapping out of it.

“We need to talk,” the little girl said.

Prader was used to Molly’s uncanny resemblance to a fully-grown adult. He hadn’t pressed for testing, but he was certain she had a genius IQ. “I’m listening,” he said.

“May I sit?”

“Of course.” He lifted his legs from the chair’s matching footstool so Molly could sit. She sat. While she situated herself, Rollie asked, “Did your mother put you up to this?”

“Put me up to what?”

“Nothing. I assumed you were going to give me some kind of pep talk,” he replied.

Molly scrunched her face. “I don’t give pep talks. Psychology is mommy’s thing. I’m more of a go-with-the-flow type of gal.”

Prader smiled slightly. He couldn’t help it. In front of him was a miniature Rosalind Russell. From His Gal Friday. “Go on…”

The girl took a breath and said, “I’ve decided to be a reverse Indian giver.”

She stated it matter-of-factly as if Rollie was supposed to know what she meant. “Wouldn’t that just be a giver?”

“Tomato, tomato. I’m not here to argue semantics.”

That did it. Rollie’s smile became a grin. He couldn’t help pitying Molly’s future husband. Unless he was some kind of brainiac, he was doomed. “Forgive me.”

“You’re forgiven. What was I talking about?”

“Indian giving.”

“Right.” Molly wore a little apron with a big front pocket. From out of this pocket, she drew a black pencil. She held it up so he could see it. “Do you remember when you gave me this?”

“I do,” he said. He wasn’t about to forget such an offbeat encounter. He wasn’t about to forget seeing his future wife for the first time.

She extended the pencil to him and said, “Here. I think you should take it back now.”

He took the pencil. “How come?”

Molly took a moment to consider. “When you first gave it to me, I thought it was magic. A whole bunch of Mickey Mouses came out of it. I’m older now, and I don’t know if I believe in magic anymore.” She had aged roughly two years since being gifted the pencil. “But—if I’m wrong—it seems like you need magic now more than I do.”

Prader didn’t like showing his emotions, but there was no hiding his moist eyes and the sob he barely stifled. “That,” he said. “Is a very kind gesture.”

Molly didn’t say anything, and Rollie marveled at the old soul behind her eyes.

“May I have a hug?”

“Certainly,” she said, getting down off the stool.

As they embraced, Rollie said, “Maybe you should consider going into the pep talk business.”

He could feel her shaking her head. “I have a very low tolerance for whining.”

“You and me both.”

The next day at work, Rollie used the magic pencil and found his flow. Time disappeared. He forgot about lunch. He didn’t even acknowledge Gary Dunmeyer. He drew so quickly that he dispensed with organization, dropping numbered drawings onto the floor.

He more than doubled his quota and knew the work was good.

When the scene went to camera and came back from the lab, it caused a sensation. The ever-prickly Ward Kimball said, “Gee, Rollie. You’re really coming into your own. And all this time I thought you were shit.”

The other men laughed. They knew that was just the way Kimball talked. You always had to take his goods with a sizable bad.

This short story is part of an interconnected series forming one “meta story”. Eventually, all of those stories will be here on Substack. If you'd like to cut to the chase, please check out the book.